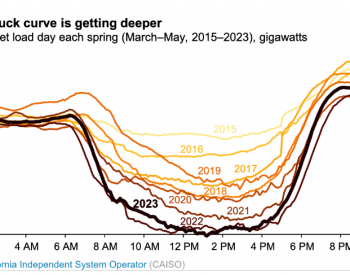

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, as solar generation has increased in California, the grid operator of the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) has seen net load (the remaining demand after subtracting variable renewable energy generation) decline on days when solar generation tends to be at its highest. When charting the load for a typical day, it can be seen that the net load curve drops sharply in the middle of the day and then rises sharply in the evening when the solar generation drops, so that the curve formed looks like the outline of a duck, so this pattern is often referred to as the "duck curve". As California's solar generation continues to grow, the decline in midday net load is increasing, creating challenges for grid operators.

Grid operators need to balance a region's generation and electricity demand at all times. Demand is lowest overnight, when most consumers are sleeping and many businesses are closed. In the morning, as people wake up and businesses open for business, demand starts to increase. Demand kept rising throughout the day, rising slightly in the evening as people returned home from work and residential electricity use increased, then falling again late at night.

However, unlike conventional power plants, such as nuclear, coal and natural gas plants, solar and wind resources cannot be deployed at will to meet demand, and utilities have at some point had to cut back on these resources to protect grid operations. Solar energy is generated only during the day, peaking at noon when the sun is at its strongest and waning at sunset. As more solar capacity comes online and conventional power plants are used less frequently in the middle of the day, the duck curve becomes more pronounced.

The duck curve implies two challenges associated with the increased use of solar energy. The first challenge is the strain on the power grid. Demand for electricity from conventional power plants fluctuates dramatically from midday to late at night, when energy demand is still high, but solar generation has declined, meaning that conventional power plants (such as natural gas plants) must rapidly increase electricity production to meet consumer demand. This rapid growth makes it harder for grid operators to match grid supply and grid demand in real time. In addition, if the amount of solar energy produced exceeds the amount used by the grid, operators may have to reduce solar power generation to prevent over-generation.

The other challenge is economic. The dynamic nature of the duck curve can challenge the traditional economics of dispatchable power plants because the factors that lead to the curve reduce the operating time of conventional power plants, resulting in reduced electricity revenue. If the loss of revenue makes plant maintenance uneconomical, the plant may be decommissioned without a dispatchable replacement. In systems where net demand fluctuates greatly, the reduction in dispatchable power makes it more difficult for grid managers to balance electricity supply and demand.

However, the duck curve also creates opportunities for energy storage. The large-scale deployment of energy storage systems, such as batteries, can store some of the solar energy generated during the day and release it after sunset. Storing solar power at noon flattens the duck's curve, and dispatching stored solar power at night shortens the duck's "neck." California is rapidly building battery storage; Growing from 0.2 GW in 2018 to 4.9 GW in April 2023, California operators are expected to build an additional 4.5 GW of battery storage capacity in the state by the end of the year.

The duck Curve is not unique to California, it is increasingly occurring in other parts of the United States and around the world, as the share of solar power generation in these places is increasing.